My latest split-off release from our super-stable FlashMQ.com PostgreSQL backend is version 1.0.0 the pg_utility_trigger_functions. It’s a very simple bundle of a bunch of trigger functions that I find useful to carry around with me, and it’s sufficiently-tested for me to bring it out immediately under a 1.0.0 stamp.

Author: Rowan Rodrik (Page 2 of 27)

Rowan is mainly a writer. This blog here is a dumping ground for miscellaneous stuff that he just needs to get out of his head. He is way more passionate about the subjects he writes about on Sapiens Habitat: the connections between humans, each other, and to nature, including their human nature.

If you are dreaming of a holiday in the forests of Drenthe (the Netherlands), look no further than “De Schuilplaats”: a beautiful vacation home, around which Rowan maintains a magnificent ecological garden and a private heather field, brimming with biological diversity.

FlashMQ is a business that offers managed MQTT hosting and other services that Rowan co-founded with Jeroen and Wiebe.

Another release from the long list of PostgreSQL extensions that I’m splitting off from the database schemas that make up our rock-solid MQTT hosting platform issss: pg_role_fkey_trigger_functions. That extension name is quite the mouthful. From its readme (again courtesy of pg_readme):

The pg_role_fkey_trigger_functions PostgreSQL extension offers a bunch of trigger functions to help establish and/or maintain referential integrity for columns that reference PostgreSQL ROLE NAMEs.

Many extensions are yet to come, because I’ve found that dependencies in themselves aren’t bad, as long as they are used side by side, and not needlessly stacked on top of each other. That they are no longer 100% internal to the migrations belonging to the app doesn’t worry my, because:

- I still maintain them myself anyway, and

- the migrations can (and will) use specific extension versions, so that, in fact, no control and cohesion is lost, even while some decoupling and modularity is being won.

Another part of my FlashMQ.com spin-off PostgreSQL extension series is pg_rowalesce. From its README.md (generated with pg_readme):

The pg_rowalesce PostgreSQL extensions its defining feature is the rowalesce() function. rowalesce() is like coalesce(), but for rows and other composite types. From its arbitrary number of argument rows, for each field/column, rowalesce() takes the value from the first row for which that particular field/column has a not null value.

pg_mockable is one of the spin-off PostgreSQL extensions that I’ve created for the backend of our high-performance MQTT hosting platform: FlashMQ. It’s basic premise is that you (through one of the helper function that the extension provides) create a mockable wrapper function around a function that you want to mock. That wrapper function will be a one-statement SQL function, so that in many cases it will be inlineable.

Then, when during testing you need to mock (for instance now() and its entire family), you can call the mockable.mock() function, which will replace that wrapper function to return the second argument fed to mockable.mock(), until mock.unmock() is called to restore the original wrapper function.

I released pg_readme a couple of days ago. From the (auto-generated, inception-style, by pg_readme) README.md:

The pg_readme PostgreSQL extension provides functions to generate a README.md document for a database extension or schema, based on COMMENT objects found in the pg_description system catalog.

This is a split-off from the PostgreSQL database structure that I’ve developed for the backend of our managed MQTT hosting platform. There will be many more of split-off PostgreSQL extensions to follow. Although I like my home-grown migration framework (soon to also be released), pushing reusable parts of schemas into separate extensions has a couple of advantages:

- easier sharing between projects;

- more decoupling between schemas, making migrations easier;

- more documentation and testing discipline due to releasing code as open source (peeing in public); and

- simpler, cleaner, more well-boundaried code.

The flashmq.com project has afforded me an opportunity to finally play with PostgREST—a technology that, for many years, I had been itching to use, even before I ever heard of PostgREST; the itch started back in the day when Wiebe and I were working with Ruby on Rails and I tried to hack ActiveRecord to propagate PostgreSQL its permissions into the controller layer, wishing to leave permission checking to the RDBMS rather than redoing everything in the controller.

One habit that changed between 2007 (when I was still working with ActiveRecord) and now (with my most recent torture being by Django’s horrid ORM) is that I no longer rely on PostgreSQL its search_path for anything. Instead, I tend to use qualified names for pretty much anything. But, because one should never stop doubting ones own choices, recently I did some digging and testing to see if there really are no valid, safe use cases for the use of unqualified names in PostgreSQL…

Before delving into the use cases, I want to ruminate on the definitional knowledge: firstly, about Postgres schemas in general, and secondly, about the search_path.

PostgreSQL schemas

- PostgreSQL enables the division of a database into namespaces called schemas.

- Schemas can contain tables, views, types, domains, functions, procedures, and operators.

- Schemas are flat, in that they cannot contain other schemas.

- Schemas are a part of the SQL standard, and, as such, other big name RDBMSs support schemas too, except, naturally, my least favorite of them all—the database I love to hate—MySQL.

- An object (such as a table) its fully qualified name consists of the schema name, followed by a dot, followed by its local name. For example: pg_catalog.pg_cast. (Incidentally, casts are one of the few types of entities that are not schema-bound.)

-

Fresh PostgreSQL databases contain a public schema by default.

- This standard public schema is part of the (modifiable) template1 database that is copied when you CREATE DATABASE (without TEMPLATE = template parameter).

-

Prior to PostgreSQL 15, the template1 database was set up such that PUBLIC (as in everyone—all roles) had CREATE permissions in the public schema.

- This was bad, mkay? The reason being CVE-2018-1058: the public schema is in the default search_path (see below), and routines in public could be created with higher specificity (and thus precedence over) their identically-named counterparts in the system-standard pg_catalog schema.

- If, for some reason, you are using Postgres its public schema, you should more likely than not REVOKE CREATE ON SCHEMA public FROM PUBLIC.

- Objects can also be identified by just their schema-local name, thanks to the search_path—a list of PostgreSQL schemas which are searched for the object name. For instance, you will see references to the now() function rather than pg_catalog.now().

PostgreSQL its effective search path and how it’s derived from the search_path setting

-

When using an unqualified object name, the schemas in the effective search path are searched, first to last.

-

The object that is selected from the searched schemas is, among those with the highest specificity, the one that is found earliest in the effective search path.

- Specificity matters, for routines and operators: a function with a better-matching type signature that is found later in the effective search path will be chosen over a more generic match that is found earlier.

-

The object that is selected from the searched schemas is, among those with the highest specificity, the one that is found earliest in the effective search path.

-

The schemas in the effective search path can be retrieved from the current_schemas(false) function.

SET search_path TO DEFAULT; SELECT current_setting('search_path'), current_schemas(false);This will give us the search_path setting side-by-side with the effective search path that is derived from it:

SET current_setting | current_schemas -----------------+----------- "$user", public | {public}-

With current_schemas(true), the implicitly-searched schemas are also included in the returned name[] array.

SET search_path TO DEFAULT; CREATE TEMPORARY TABLE a (id INT); SELECT current_setting('search_path'), current_schemas(true);SET CREATE TABLE current_setting | current_schemas -----------------+------------------------------- "$user", public | {pg_temp_3,pg_catalog,public} (1 row)

-

With current_schemas(true), the implicitly-searched schemas are also included in the returned name[] array.

-

The effective search path is derived from the search_path setting:

-

Schemas that don’t exist or are inaccessible to the current_user are subtracted from the search_path.

CREATE SCHEMA need_to_know_basis; CREATE ROLE no_need_to_know; GRANT USAGE ON SCHEMA public TO no_need_to_know; SET ROLE TO no_need_to_know; SET search_path TO need_to_know_basis, "$user", public; SELECT current_setting('search_path'), current_schemas(false);CREATE SCHEMA CREATE ROLE GRANT SET SET current_setting | current_schemas -------------------------------------+----------------- need_to_know_basis, "$user", public | {public} (1 row) -

"$user" is expanded into current_user if a schema by that name exists and is accessible to the current user:

DROP ROLE IF EXISTS bondjames; DROP SCHEMA IF EXISTS bondjames; CREATE ROLE bondjames; CREATE SCHEMA AUTHORIZATION bondjames; SET ROLE TO bondjames; SET search_path TO DEFAULT; SELECT current_setting('search_path'), current_schemas(false);CREATE ROLE CREATE SCHEMA SET SET current_setting | current_schemas -----------------+----------------- "$user", public | {bondjames} (1 row) -

pg_catalog is always included in the effective search path.

-

If pg_catalog is not explicitly included in the search_path, it is implicitly prepended to the very beginning of the search_path:

SET search_path TO DEFAULT; SELECT current_setting('search_path'), current_schemas(true);SET current_setting | current_schemas -----------------+--------------------- "$user", public | {pg_catalog,public} (1 row)

-

If pg_catalog is not explicitly included in the search_path, it is implicitly prepended to the very beginning of the search_path:

-

pg_temp is also included in the effective search path, if it exists—that is, if any temporary objects have been created.

- When pg_temp is omitted from the explicit search_path setting, it is prepended implicitly in front of the search_path, even before pg_catalog.

- pg_temp is expanded into the actual pg_temp_nnn for the current session.

-

“[T]he temporary schema is only searched for relation (table, view, sequence, etc.) and data type names. It is never searched for function or operator names.”

-

This default behavior—to never search pg_temp for function names and operators—was introduced in 2007 in response to CVE-2007-2138. From the release notes:

“This [was] needed to allow a security-definer function to set a truly secure value of search_path. Without it, an unprivileged SQL user can use temporary objects to execute code with the privileges of the security-definer function (CVE-2007-2138). See CREATE FUNCTION for more information.”

-

This default behavior—to never search pg_temp for function names and operators—was introduced in 2007 in response to CVE-2007-2138. From the release notes:

-

Schemas that don’t exist or are inaccessible to the current_user are subtracted from the search_path.

-

The default Postgres search_path is:

SET search_path TO DEFAULT; SELECT current_setting('search_path'); SHOW search_path;SET current_setting ----------------- "$user", public (1 row) search_path ----------------- "$user", public (1 row)

Routine-specific search_path settings

Like many settings in PostgreSQL, search_path can be set on many levels:

-

In the postgresql.conf config file:

search_path = '"$user", public'

-

At the user/role level:

ALTER ROLE { role_specification | ALL } [ IN DATABASE database_name ] SET search_path { TO | = } { value | DEFAULT } ALTER ROLE { role_specification | ALL } [ IN DATABASE database_name ] SET search_path FROM CURRENT ALTER ROLE { role_specification | ALL } [ IN DATABASE database_name ] RESET search_path

-

At the database level:

ALTER DATABASE name SET search_path { TO | = } { value | DEFAULT }; ALTER DATABASE name SET search_path FROM CURRENT; ALTER DATABASE name RESET search_path;

-

And at the routine level:

ALTER FUNCTION name [ ( [ [ argmode ] [ argname ] argtype [, ...] ] ) ] SET search_path { TO | = } { value | DEFAULT }; ALTER FUNCTION name [ ( [ [ argmode ] [ argname ] argtype [, ...] ] ) ] SET search_path FROM CURRENT; ALTER FUNCTION name [ ( [ [ argmode ] [ argname ] argtype [, ...] ] ) ] RESET search_path; ALTER PROCEDURE name [ ( [ [ argmode ] [ argname ] argtype [, ...] ] ) ] SET search_path { TO | = } { value | DEFAULT }; ALTER PROCEDURE name [ ( [ [ argmode ] [ argname ] argtype [, ...] ] ) ] SET search_path FROM CURRENT; ALTER PROCEDURE name [ ( [ [ argmode ] [ argname ] argtype [, ...] ] ) ] RESET search_path;

- within SECURITY INVOKER routines, because these are executed with the privileges of the caller (but see below for further caveats);

- within SECURITY DEFINER routines for which SET search_path is explicitly specified;

- within CREATE TABLE and CREATE VIEW DDL statements, as long as you are aware of the search_path at the time of creation, as the schema-binding will happen during creation.

- when there are schemas in the search_path which you do not trust 100%;

- within SECURITY DEFINER routines for which SET search_path is not explicitly specified;

- (trigger) routines that are supposed to produce something random (unless if these are protected by SET search_path;

- The Schemas section in the Data Definition chapter.

- The search_path setting in the Client Connection Defaults documentation

- The Writing SECURITY DEFINER Functions Safely section in the CREATE FUNCTION documentation.

-

The Session Information Functions table in the System Information Functions and Operators section documents

-

the current_schema() function

- (and its current_schema alias),

- as well as current_schemas().

-

the current_schema() function

-

CVE-2007-2138 resulted in 2 changes:

- “Support explicit placement of the temporary-table schema within search_path”

- “and disable searching it for functions and operators (Tom)”.

-

CVE-2018-1058 initially resulted only in additional documentation to explain user how to avoid this type of attack: A Guide to CVE-2018-1058: Protect Your Search Path

- Years later, in PostgreSQL 15, the vanilla template1 database was changed to no longer GRANT CREATE ON SCHEMA public TO PUBLIC.

Importantly, all these settings set defaults. They do not stop the user (or a VOLATILE function/procedure) from overriding that default by issuing:

SET search_path TO evil_schema, pg_catalog;

Or, if the user doesn’t have their own evil_schema:

select set_config('search_path', 'pg_temp, pg_catalog');

In the following example, SUPERUSER wortel innocuously uses lower() in a SECURITY DEFINER function, naively assuming that it’s implicitly referring to pg_catalog.lower():

CREATE ROLE wortel WITH SUPERUSER; SET ROLE wortel; CREATE SCHEMA myauth; GRANT USAGE ON SCHEMA myauth TO PUBLIC; CREATE FUNCTION myauth.validate_credentials(email$ text, password$ text) RETURNS BOOLEAN SECURITY DEFINER LANGUAGE PLPGSQL AS $$ DECLARE normalized_email text; BEGIN normalized_email := lower(email$); -- Something interesting happens here… RETURN TRUE; END; $$; GRANT EXECUTE ON FUNCTION myauth.validate_credentials TO PUBLIC;

wortel creates a new user piet and gives piet his own schema, assuming that he can only do damage to his own little garden:

CREATE ROLE piet; CREATE SCHEMA AUTHORIZATION piet;

However, piet turns out to be wearing his black hat today:

SET ROLE piet;

SET search_path TO DEFAULT;

SELECT current_setting('search_path'), current_schemas(true);

SELECT myauth.validate_credentials('pietje@example.com', 'Piet zijn password');

CREATE FUNCTION piet.lower(text)

RETURNS TEXT

LANGUAGE plpgsql

AS $$

BEGIN

RAISE NOTICE 'I can now do nasty stuff as %!', current_user;

RETURN pg_catalog.lower($1);

END;

$$;

SET search_path TO piet, pg_catalog; -- Reverse order;

SELECT current_setting('search_path'), current_schemas(true);

SELECT myauth.validate_credentials('pietje@example.com', 'Piet zijn password');

SET

SET

current_setting | current_schemas

-----------------+-------------------

"$user", public | {pg_catalog,piet}

(1 row)

validate_credentials

----------------------

t

(1 row)

CREATE FUNCTION

SET

current_setting | current_schemas

------------------+-------------------

piet, pg_catalog | {piet,pg_catalog}

(1 row)

NOTICE: I can now do nasty stuff as superuser!

validate_credentials

----------------------

t

(1 row)

This can be mitigated by attaching a specific search_path to the SECURITY DEFINER routine:

RESET ROLE;

ALTER FUNCTION myauth.validate_credentials

SET search_path = pg_catalog;

SET ROLE piet;

SET search_path TO piet, pg_catalog; -- Reverse order;

SELECT current_setting('search_path'), current_schemas(true);

SELECT myauth.validate_credentials('pietje@example.com', 'Piet zijn password');

RESET

ALTER FUNCTION

SET

SET

current_setting | current_schemas

------------------+-------------------

piet, pg_catalog | {piet,pg_catalog}

(1 row)

validate_credentials

----------------------

t

(1 row)

Before the changes made in response to CVE-2007-2138, piet would have been able to mask pg_catalog.lower with his own pg_temp.lower() even if he did not muck around with the search_path. After all, by default, pg_temp is prepended to the very front of the effective search path:

CREATE ROLE wortel WITH SUPERUSER;

SET ROLE wortel;

CREATE SCHEMA myauth;

GRANT USAGE

ON SCHEMA myauth

TO PUBLIC;

CREATE FUNCTION myauth.validate_credentials(email$ text, password$ text)

RETURNS BOOLEAN

SECURITY DEFINER

LANGUAGE PLPGSQL

AS $$

DECLARE

normalized_email text;

BEGIN

normalized_email := lower(email$);

-- Something interesting happens here…

RAISE NOTICE 'My effective search path is: %', current_schemas(true);

RETURN true;

END;

$$;

GRANT EXECUTE

ON FUNCTION myauth.validate_credentials

TO PUBLIC;

DROP SCHEMA piet CASCADE;

DROP ROLE piet;

CREATE ROLE piet;

SET ROLE piet;

SET search_path TO DEFAULT;

SELECT current_setting('search_path'), current_schemas(true);

SELECT myauth.validate_credentials('pietje@example.com', 'Piet zijn password');

CREATE FUNCTION pg_temp.lower(text)

RETURNS TEXT

LANGUAGE plpgsql

AS $$

BEGIN

RAISE NOTICE 'I can now do nasty stuff as %!', current_user;

RETURN pg_catalog.lower($1);

END;

$$;

SELECT current_setting('search_path'), current_schemas(true);

SELECT myauth.validate_credentials('pietje@example.com', 'Piet zijn password');

RESET ROLE;

ALTER FUNCTION myauth.validate_credentials

SET search_path = pg_catalog;

SET ROLE piet;

SELECT current_setting('search_path'), current_schemas(true);

SELECT myauth.validate_credentials('pietje@example.com', 'Piet zijn password');

CREATE ROLE

SET

CREATE SCHEMA

GRANT

CREATE FUNCTION

GRANT

ERROR: schema "piet" does not exist

DROP ROLE

CREATE ROLE

SET

SET

current_setting | current_schemas

-----------------+-----------------

"$user", public | {pg_catalog}

(1 row)

NOTICE: My effective search path is: {pg_catalog,public}

validate_credentials

----------------------

t

(1 row)

CREATE FUNCTION

current_setting | current_schemas

-----------------+------------------------

"$user", public | {pg_temp_3,pg_catalog}

(1 row)

NOTICE: My effective search path is: {pg_temp_3,pg_catalog,public}

validate_credentials

----------------------

t

(1 row)

RESET

ALTER FUNCTION

SET

current_setting | current_schemas

-----------------+------------------------

"$user", public | {pg_temp_3,pg_catalog}

(1 row)

NOTICE: My effective search path is: {pg_temp_3,pg_catalog}

validate_credentials

----------------------

t

(1 row)

As you can see, now this approach doesn’t work anymore, even though the effective search path includes pg_temp_3 (logically so because it is omitted in the search_path that is SET on the routine level). That is because part of the fix for CVE-2007-2138 was that unqualified routine and function names are never searched for in the temporary schema name. (The other part of the fix was that pg_temp can be listed explicitly in the search_path to also give it lower precedence for relation names.)

Before PostgreSQL 15, there was another way in which piet would have been able to mask pg_catalog.lower(): by creating the function in public, which was, until Pg 15, fair game for all roles to CREATE FUNCTIONs in.

Pro tip: you can use CREATE { FUNCTION | ROUTINE } … SET search_path FROM CURRENT to take the search_path from the migration context.

When unqualified names in table column default value expressions are evaluated

So, now we know how to control the search_path of tables so that we don’t have to write out every operator within each function in a form like:

SELECT 3 OPERATOR(pg_catalog.+) 4;

How about the DEFAULT expressions for columns in table definitions? And, similarly, what about GENERATED ALWAYS AS expressions?

If a table is wrapped inside a view for security, can evil_user mask, for instance, the now() function with evil_user.now() and have evil_user.now() be executed as the view’s definer?

No:

“Functions called in the view are treated the same as if they had been called directly from the query using the view. Therefore, the user of a view must have permissions to call all functions used by the view. Functions in the view are executed with the privileges of the user executing the query or the function owner, depending on whether the functions are defined as SECURITY INVOKER or SECURITY DEFINER. Thus, for example, calling CURRENT_USER directly in a view will always return the invoking user, not the view owner. This is not affected by the view’s security_invoker setting, and so a view with security_invoker set to false is not equivalent to a SECURITY DEFINER function and those concepts should not be confused.”

But is the same true for when the table is wrapped by one of these MS Certified Suit-style wrapper functions? This would depend on when the unqualified object names are resolved into schema-qualified names—during table definition or during INSERT or UPDATE. So when does this happen? Well, that is a bit difficult to spot:

BEGIN TRANSACTION;

CREATE ROLE wortel WITH SUPERUSER;

SET ROLE wortel;

CREATE SCHEMA protected;

CREATE SEQUENCE protected.thingy_id_seq;

CREATE TABLE protected.thingy (

id BIGINT

PRIMARY KEY

DEFAULT nextval('protected.thingy_id_seq')

,id2 UUID

UNIQUE

DEFAULT gen_random_uuid()

,inserted_by_application NAME

DEFAULT current_setting('application_name')

,inserted_at TIMESTAMPTZ

DEFAULT now()

,description TEXT

);

SELECT pg_get_expr(adbin, 'protected.thingy'::regclass::oid)

FROM pg_catalog.pg_attrdef

WHERE adrelid = 'protected.thingy'::regclass::oid;

CREATE SCHEMA exposed;

CREATE FUNCTION exposed.insert_thingy(TEXT)

RETURNS BIGINT

SECURITY DEFINER

LANGUAGE PLPGSQL

AS $$

DECLARE

_new_id BIGINT;

BEGIN

RAISE NOTICE 'current_schemas(true) = %', current_schemas(true);

INSERT INTO protected.thingy (description)

VALUES ($1)

RETURNING id

INTO _new_id;

RETURN _new_id;

END;

$$;

CREATE ROLE evil_user;

CREATE SCHEMA AUTHORIZATION evil_user;

GRANT USAGE

ON SCHEMA exposed

TO evil_user;

GRANT EXECUTE

ON FUNCTION exposed.insert_thingy

TO evil_user;

SET ROLE evil_user;

CREATE FUNCTION evil_user.nextval(regclass)

RETURNS BIGINT

LANGUAGE PLPGSQL

AS $$

BEGIN

RAISE NOTICE 'I am now running as: %', current_user;

RETURN 666;

END;

$$;

CREATE FUNCTION evil_user.now()

RETURNS TIMESTAMPTZ

LANGUAGE PLPGSQL

AS $$

BEGIN

RAISE NOTICE 'I am now running as: %', current_user;

RETURN pg_catalog.now();

END;

$$;

SET search_path TO evil_user, pg_catalog; -- Reverse path

SELECT exposed.insert_thingy('This is a thing');

RESET ROLE;

SHOW search_path;

SELECT pg_get_expr(adbin, 'protected.thingy'::regclass::oid)

FROM pg_catalog.pg_attrdef

WHERE adrelid = 'protected.thingy'::regclass::oid;

BEGIN

CREATE ROLE

SET

CREATE SCHEMA

CREATE SEQUENCE

CREATE TABLE

pg_get_expr

----------------------------------------------

nextval('protected.thingy_id_seq'::regclass)

gen_random_uuid()

current_setting('application_name'::text)

now()

(4 rows)

CREATE SCHEMA

CREATE FUNCTION

CREATE ROLE

CREATE SCHEMA

GRANT

GRANT

SET

CREATE FUNCTION

CREATE FUNCTION

SET

NOTICE: current_schemas(true) = {evil_user,pg_catalog}

insert_thingy

---------------

1

(1 row)

RESET

search_path

-----------------------

evil_user, pg_catalog

(1 row)

pg_get_expr

---------------------------------------------------------

pg_catalog.nextval('protected.thingy_id_seq'::regclass)

gen_random_uuid()

current_setting('application_name'::text)

pg_catalog.now()

(4 rows)

As you can see, pg_get_expr() has only disambiguated the functions that evil_user has tried to mask. Conclusion: yes, schema-binding happens when the DDL (CREATE or ALTER TABLE) is executed.

No need to worry about security holes here, as long as you are aware of the search_path with which you are running your migrations. (You are using some sort of migration script, are you not? The only valid answer in the negative is if instead you’re managing your PostgreSQL schemas via extension upgrade scripts.)

Valid and less valid search_path use cases

Despite the deep-dive in all the caveats above, the search_path is not all bad. We can now be very precise about the context in which it’s reasonably safe to rely on the search_path:

Do note that even without escalated privileges, the unsuspected masking of a function by a malicious function could still result in, for instance, prices for a certain user always amounting to zero, or the random password reset string being not so random. Therefore, here are some context in which you should never rely on the search_path:

That all sounds terribly complicated. That begs the question: are there, in fact, use cases which would justify us to not just blanket schema-qualify ever-y-thing?

Use case: brevity

If you consider that operators are schema-qualified objects too, you will most likely want to at least allow yourself and your team to forego the typing of 3 + 4 instead of 3 OPERATOR(pg_catalog.+) 4 in the body of your routines. Admittedly, this is not a very strong argument in favor of the search_path, but there is no harm in it as long as your define your routines with SET search_path.

Use case: polymorphism

When I define a poymorphic routine with anyelement, anyarray or anyanything pseudo-types in its signature, I want the routine to be able to apply functions and operators to its arguments regardless of whether these (overloaded) functions and operators already existed in a schema that I was aware of at the time of CREATE-ing the routine.

Suppose I have a polymorphic function called sum_price_lines(anyarray):

BEGIN TRANSACTION;

CREATE FUNCTION pricing.sum_price_lines(anyarray)

RETURNS anyelement

LANGUAGE plpgsql

AS $$

BEGIN

RETURN (

SELECT

SUM(net_price(line))

FROM

unnest($1) AS line

);

END;

$$;

CREATE FUNCTION pricing.net_price(int)

RETURNS int

LANGUAGE SQL

RETURN $1;

SET search_path TO pricing;

SELECT pricing.sum_price_lines('{1,2,3,4}'::int[])

sum_price_lines() calls net_price on each individual member of its anyarray argument. With the supplied function, this doesn’t do anything useful, but the creator of the invoicing schema can for instance use this to sum rows of the invoicing.invoice_line table type, simply by creating an overloaded invoicing.net_price(invoicing.invoice_line[]) function and making sure that it can be found in the search_path.

Use case: function and operator overloading

And indeed overloading (also of operators) is a very important use case of the search_path. Being able to define +, -, and * for anything, from order lines, to invoice lines, to quotation lines, and to users even is a valuable tool, that we wouldn’t want to be taken away from us entirely by a lacking understanding of search_path security.

Use case: overriding/masking objects in another schema

I got re-interested in relying on the search_path rather than on schema-qualified names while I was working on an extension to make mocking the pg_catalog.now() function (or other functions) easy and performant. Because table defaults are schema-bound during CREATE TABLE time, I couldn’t rely on the search_path to mask pg_catalog.now() with mockable.now(). Instead, I use mockable.now() directly, which, when the mocker is not active, is just a thin wrapper around pg_catalog.now(), which the query planner should be able to inline completely without trouble.

But there are other use cases in which schema masking can be very useful. For instance, if you want to offer a specific extension schema to your … extension. Maybe you want to offer a table with factory defaults and rather than have the user TRUNCATE the table (and make upgrades and comparisons to the factory-default data a headache), you allow them (or some function/producedure, possible triggered from a view) to create a table of their own. Let me know if you know or can come up with more good examples.

Some words of thanks

Thanks to the Postgres ecosystem

I wish to express my gratitude towards the ever-solid developers of PostgreSQL, who have kept improving PostgreSQL at a steady, sustainable pace in the 15 years since I last seriously used it in 2007. All the features that I wished were there in 2007 have since been implemented, including, very recently, in PostgreSQL, WITH (security_invoker) for views. A guilty pleasure from my last long-term stint at a wage slave working with Django’s ORM was to every now and then glare at the PostgreSQL feature matrix and fantasize about being able to really unleash this beast without being hindered by the lowest common denominator (MySQL) that ORMs tend to cater to.

And thanks to the excellent PostgREST, I can now do what I dreamt of for years. And yes, for years, I’ve dreamt precisely of using PostgREST rather than all the ridiculously inefficient, verbose, and mismatched layers around SQL that things like the django-rest-framework forced upon me. Indeed, as François-Guillaume Ribreau testified, “it feels like cheating!”

Thanks to friends

The motivation for deep-diving into PostgreSQL again, after quite a few years wherein the power of PostgreSQL was buffered by Django in my day job, came from an excellent MQTT broker written by my buddy Wiebe. Me and another friend—Jeroen—where so impressed by the speed and robustness of this MQTT server software that we decided to build a managed MQTT hosting business around it. And we’ve been building all this goodness around the FlashMQ FOSS core with a very solid PostgreSQL core, a PostgREST API and a Vue.JS/Nuxt front + back-end. Some daemons hover around the PostgreSQL core and connect directly to it (through dedicated schemas, to confirm to my Application-Exclusive Schema Scoping (AESS) practice), so that it all resembles a very light-weight micro-services architecture.

Further reading

Recently, I was digging in the possibilities of using PostgreSQL’s set_config() and current_setting() functions when I stumbled upon a Stack Overflow question detailing pretty much the research I was doing for myself. My answer was rather elaborate, which is why I’m linking it here to find it back with more ease than through the SO interface.

For a decade and a half, my uncle had been maintaining the website for our vacation home in the forests of Drenthe in Dreamweaver. This worked fine, except that:

- it didn’t allow me to edit and add content and photos simultaneously;

- the website had started to look and feel dated;

- it wasn’t mobile-ready; and

- all this was affecting its ranking in Google.

That’s why I had been having a new WordPress website in the pipeline since forever. However, in true 80/20 fashion, I was postponing the final steps of copying over the last bits of content and the training of my uncle to edit the website in WordPress instead of in Dreamweaver.

Why WordPress?

The last few websites I built I built myself from scratch, like in the good old days, using a simple static site generation pipeline (basically a fancy Makefile). The reasoning is that comments are too much hassle to moderate anyway, and comments and trackbacks are what WordPress offered me. Apart from that I very much prefer authoring in vim.

But that’s me. Most people, my uncle included, are way more comfortable with WYSIWYG editors—in other words: WordPress its Gutenberg editor.

A mature developer has to be able to sidestep his preferences to deliver something that’s best for the “customer”. (Indeed this post will be me bragging of how mature a developer I am. I do turn 40 tomorrow after all.)

My main “design” goal was that I didn’t want to change too much at once. The site structure and site content had to remain mostly identical, so that we would have fewer points of discussion to surmount before going live.

At the same time, I did want to clean up the content and the formatting. The old website had a distinct lack of bullets, formal headings, use of bold text, etc. (No, I don’t have pictures.) That made the text a bit difficult to parse, especially when the visitor—a potential tenant of our forest home—was just trying to find a specific piece of information at a glance.

The new website is not fancy. The theme is just one of WordPress its default themes, and I ended up not even using a graphical header to get the first version online. Important to me is that I can now easily add blog posts (like about a pretty yellow flower that I got to grow there abundantly). Also, whenever now I want to edit some text in one of the informational pages, I can.

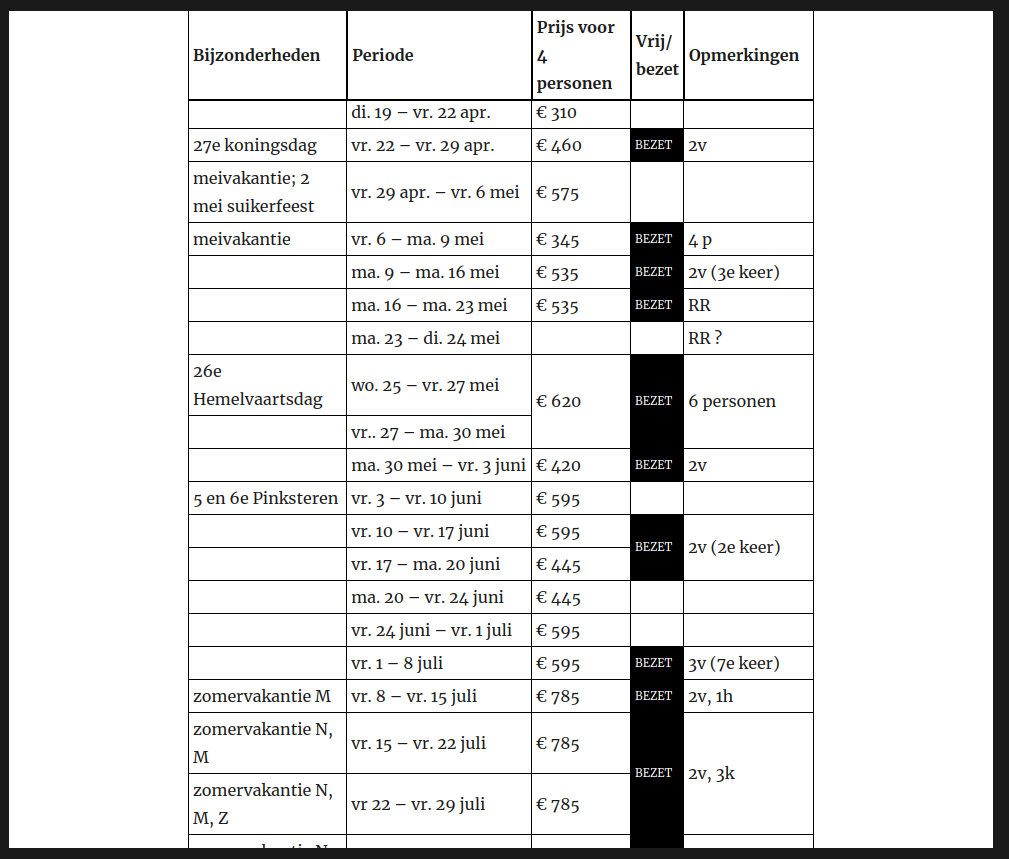

The “page with booking information and booking availability gave me the most headaches and demanded the most from my maturity. The first thing to swipe off the table was the use of any type of booking plugin. This turned out to be the most important decision (and a very good call!). The old website (with light-yellow background) had one of those old-fashioned tables with big-ridged borders around every cell. I wanted to at least make this table look good and modern.

I gave the booking periods table a sticky header. That was something at least. What I did not do was giving the individual cells a border. But, as much as he tried liking it, my uncle hated that incarnation of the table. So I put back in some cell borders, which I had already done in the print CSS version.

Then there was the issue that my uncle had gotten used to printing out the booking schedule, and it now spanned a number of pages. Thus I did a lot of tinkering in the print CSS to make it all fit (and to make the table header repeat, just in case). And it turned that both cleaning ladies didn’t like the spacious table layout on the screen either. I had altogether forgot about them as consumers of the table, focusing instead on potential tenants. More squeezing followed, until everybody was happy, and I was … relieved.

It deserves mentioning that I did all these CSS within WordPress its theme customizer. Normally, I would have preferred to use a child theme for this, but it felt to early to start a child-theme, as long as I haven’t fully committed to a particular parent theme. Also, the CSS for that booking schedule table is some of the worst you might have seen. After all, the HTML is not semantic at all. It’s not like I’m going to train my uncle to specify class names on each cell. Without proper classification, I had to use implicit classification, ending up with selectors such as the td:nth-child(4):not([colspan]):not(:empty) selector that I use to make the background of occupied periods black, but only if they are not some special multi-column note. To scare the CSS wizards out there, here’s the current CSS for the table:

@media screen {

table.wp-block-advgb-table.advgb-table-frontend {

border-width: 0;

border-spacing: 0;

border-collapse: separate;

table-layout: auto;

}

.wp-block-advgb-table > thead > tr {

position: sticky;

top: 0;

}

.wp-block-advgb-table > thead > tr > th {

background-color: white;

box-sizing: border-box;

border-top: 1px solid black;

border-left: none;

border-right: 1px solid black;

border-bottom: 2px solid black;

padding: 2px 4px;

}

.wp-block-advgb-table > thead > tr > th {

border-left: 1px solid black;

}

.wp-block-advgb-table > tbody > tr > td {

border-top: none;

border-left: none;

border-right: 1px solid black;

border-bottom: 1px solid black;

padding: 2px 4px;

}

.wp-block-advgb-table > tbody > tr > td:first-child {

border-left: 1px solid black;

}

.wp-block-advgb-table > tbody > tr > td:nth-child(4):not([colspan]) {

width: 2em;

font-size: 70%;

}

.wp-block-advgb-table > tbody > tr > td:nth-child(4):not([colspan]):not(:empty) {

background-color: black;

color: white;

}

.wp-block-advgb-table > tbody > tr > td[rowspan] {

}

}

@media screen and (max-width: 1000px) {

table.wp-block-advgb-table.advgb-table-frontend {

position: relative;

left: -7.6923%;

max-width: none;

font-size: 70%;

}

.wp-block-advgb-table > thead > tr > th, .wp-block-advgb-table > tbody > tr > td {

padding: 0px 1px;

}

.wp-block-advgb-table > thead > tr > th {

overflow-wrap: break-word;

}

.wp-block-advgb-table > thead > tr > th:nth-child(3) {

font-size: 0; /* ugly hack to hide regular text. */

}

.wp-block-advgb-table > thead > tr > th:nth-child(3):after {

content: 'Prijs';

font-size: 12px; /* ugly override because percentage would be percentage of 0. */

}

.wp-block-advgb-table > thead > tr > th:nth-child(4) {

font-size: 0; /* ugly hack to hide regular text. */

}

.wp-block-advgb-table > thead > tr > th:nth-child(4):after {

content: 'Vrij?';

font-size: 12px; /* ugly override because percentage would be percentage of 0. */

}

.wp-block-advgb-table > tbody > tr > td:first-child {

min-width: 8ch;

max-width: 12ch;

}

.wp-block-advgb-table > tbody > tr > td:nth-child(2) {

word-spacing: -.2ch;

min-width: 15ch;

max-width: 20ch;

}

}

@media screen and (min-width: 1001px) { .wp-block-advgb-table > thead > tr {

top: 21px; /* Space from the theme that somehow has a weird z-indexy effect. */

}

body.admin-bar .wp-block-advgb-table > thead > tr {

top: calc(31px + 21px);

}

.wp-block-advgb-table > tbody > tr > td:nth-child(2) {

white-space: nowrap;

max-width: 20em;

}

}

/* filter bypass hack */@media print {

.wp-block-advgb-table.advgb-table-frontend {

width: 100%;

border: 1pt solid black important!;

border-spacing: 0;

border-collapse: collapse;

font-size: 8pt;

table-layout: auto;

}

.wp-block-advgb-table > thead > tr > th {

border: 2pt solid black !important;

padding: 2pt 4pt;

}

table.wp-block-advgb-table > tbody > tr > td {

border: 1pt solid black !important;

padding: 1pt 4pt;

}

.wp-block-advgb-table > tbody > tr > td:first-child {

white-space: nowrap;

}

.wp-block-advgb-table > thead > tr > th:nth-child(3) {

font-size: 0; /* ugly hack to hide regular text. */

}

.wp-block-advgb-table > thead > tr > th:nth-child(3):after {

content: 'Prijs';

font-size: 12px; /* ugly override because percentage would be percentage of 0. */

}

.wp-block-advgb-table > thead > tr > th:nth-child(4) {

font-size: 0; /* ugly hack to hide regular text. */

}

.wp-block-advgb-table > thead > tr > th:nth-child(4):after {

content: 'Vrij?';

font-size: 12px; /* ugly override because percentage would be percentage of 0. */

}

.wp-block-advgb-table > tbody > tr > td:nth-child(3) {

max-width: 8ch;

}

}

Which reminds me of something quite terrible about Gutenberg. Its table block doesn’t support merged cells, like—what the fuck?—why is this not considered a priority? Fucking hipsters and their having to reinvent the wheel every year and taking years to put all the spokes back into place. The “solution” was to install a plugin—PublishPress Blocks—that among other blocks that I don’t need (and could thankfully turn off) an “Advanced Table Block” that does support cell merging, but with such nasty bugs that it’s really hard to train my uncle to work around them. Sadly, there has been no activity yet to fix either one of them.

That’s it. This project didn’t make me more of a WordPress fan. (I’m no hater either. I think that WordPress its UX, specifically, has long been excellent, and exemplary in its non-nerdiness, quite the contrast with other popular open source CMSs.) But I chose the right tool for the right job and managed to make myself and the other “customers” happy. Since the go-live, I’ve added a number of blog posts already, and it’s great fun to now be able to contribute to this website’s content.

Did this get you interested? Feel free to book a stay in our idyllic vacation home in Norg, Drenthe, the Netherlands

Now that I am dedicated to becoming a somewhat decent C programmer, I need to master pointers. Last week, I leveled up in my pointer usage by debugging a particularly nasty segfault. It took the help of gdb (the GNU Project Debugger) for me to notice that my segfault was accompanied by very weird values for some increment counters, while the pointer involved was a char* pointer, not a pointer to an int.

GDB

First, some notes on the GNU Project Debugger: it’s excellent! And … it’s easy to use. I have no idea why looong ago, when as a budding programmer I was trying to use it, I had so much trouble using it that it stuck into my memory as a very tough tool to use. Well, this is not the same brain anymore, so time to get rid of all these printf() statements everywhere (that I wouldn’t dare use in a programming language that I do have some fluency in, mind you!) [lines of shame: L45, L100, L101, L119 ].

With the help of gdb xjot-to-xml (and then, from within GDB, run < my-test-file.xjot), I noticed that some of the ints I used to track byte, line and column positiion had ridiculously high values for the input line, especially since I was pretty sure that my program crashed already on the first character.

In GDB, such things are easy to find out: you can very simply set a breakpoint anywhere:

break 109 run < tests/element-with-inline-content.xjot

Starting program: /home/bigsmoke/git/xjot/xjot-to-xml < tests/element-with-inline-content.xml

a

b

Breakpoint 1, _xjot_to_xml_with_buf (in_fd=537542260, out_fd=1852140901, buf=0x6c652d746f6f723c, buf_size=1024)

at xjot_to_xml.c:109

109 byte = ((char*)buf)[0];

From there, after hitting the breakpoint, I can check the content of the variable n that holds the number of bytes read by read() into buf.

print n

$1 = 130

So, the read() function had read 130 bytes into the buffer. Which makes sense, because element-with-inline-content.xjot was 128 characters, and the buffer, at 1024 bytes, is more than sufficient to hold it all.

But, then line_no and col_no variables:

(gdb) print line_no $2 = 1702129263 (gdb) print col_no $4 = 1092645999

It took me a while to realize that this must have been due to a buffer overrun. Finally, I noticed that I was feeding the address of the buf pointer to read() instead of the value of the pointer.

(I only just managed to fix it before Wiebe, out of curiosity to my C learning project, glanced at my code and immediately spotted the bug.)

The value of pointers

C is a typed language, but that doesn't mean that you cannot still very easily shoot yourself in the foot with types, and, this being C, it means that it's easiest to shoot yourself in the foot with the difference between pointers and non-pointers.

I initialized my buffer as a plain char array of size XJOT_TO_XML_BUFFER_SIZE_IN_BYTES. Then, the address of that array is passed to the _xjot_to_xml_with_buf() function. This function expects a buf parameter of type void*. (void* pointers can point to addresses of any type; I picked this “type”, because read() wants its buffer argument to be of that type.)

What went wrong is that I then took the address of void* buf, which is already a pointer. That is to say: the value of buf is the address of buffer which I passed to _xjot_to_xml_with_buf() from xjot_to_xml().

When I then took the address of the void* buf variable itself, and passed it to read(), read() started overwriting the memory in the stack starting at that address, thus garbling the values of line_no and col_no in the process.

The take-home message is: pointers are extremely useful, once you develop an intuition of what they're pointing at. Until that time, you must keep shooting yourself in the foot, because errors are, as Huberman says, the thing that triggers neuroplasticity.

Since the beginning of this month (October 2021), I become officially jobless, after 6 years at YTEC. That’s not so much of a problem for a software developer in 2021—especially one in the Dutch IT industry, where there has been an enormous shortage of skilled developers for years. However… I don’t (yet) want a new job as a software developer, because: in the programming food pyramid, I’m a mere scripter. That is, the language in which I’m most proficient are all very high-level languages: Python, PHP, XSLT, Bash, JavaScript, Ruby, C# (in order of decreasing (recency of) experience. I have never mastered a so-called systems language: C, C++, Rust.

Now, because of the circumstances in which YTEC and I decided to terminate the contract, I am entitled to government support until I find a new job. During my last job, I’ve learned a lot, but almost all I learned made me even more high-level and business-leaning than I already was. I’ve turned into some sort of automation & integration consultant / business analyst / project manager. And, yes, I’ve sharpened some of my code organization, automated testing skills as well. Plus I now know how to do proper monitoring. All very nice and dandy. But, what I’m still missing are ① hardcore, more low-level technical skills, as well as ② front-end, more UX-oriented skills. Only with some of those skills under my belt will I be able to do the jobs I really want to do—jobs that involve ① code that has to actually work efficient on the hardware level—i.e., code that doesn’t eat up all the hardware resources and suck your battery (or your “green” power net) empty; and I’m interested in making (website) application actually pleasant (and accessible!) to use.

If I start applying for something resembling my previous job, I will surely find something soon enough. However, first I am to capture these new skills, if I also wish to continue to grow my skill-level, my self-respect, as well as my earning (and thus tax paying) potential. Hence, the WW challenge. WW is the abbreviation for Wet Werkeloosheid, a type of welfare that Dutchies such as myself get when they temporarily are without job, provided that you were either ⓐ fired or ⓑ went away in “mutual understanding” (as I was). If ⓒ you simply quit, you don’t have the right to WW (but there are other fallbacks in the welfare state of the NL).

Anyways, every month, I have to provide the UWV—the governmental organization overseeing people in the WW—with evidence of my job-seeking activities. Since I decided that I want to deepen my knowledge instead of jumping right back into the pool of IT minions, I will set myself challenges that require the new skills I desire.

My first goal is to become more comfortable with the C programming language. I have some experience with C, but my skill level is rudimentary at best. My most recent attempt to become more fluent in C was that I participated in the 2020 Advent of Code challenge. I didn’t finish that attempt, because, really, I’m a bread programmer. Meaning: before or after a 8+-hour day at the office, I have very little desire to spend my free time doing even more programming. To stay sane (and steer clear of burnout), that time is much-needed for non-digital activities in social space, in nature, and by inhabiting my physical body.

So now I do have time and energy to learn some new skills that really require sustained focus over longer periods of time to acquire. On the systems programming language level, besides C, I’m also interested in familiarizing myself with C++ and Rust. And it is a well-known facts that C knowledge transfers very well to these two languages.

Okay, instead of doing silly Christmas puzzles, this time I’ve resumed my practice by writing an actual program in C that is useful to me: xjot-to-xml. It will be a utility to convert XJot documents to regular XML. XJot is an abbreviated notation for XML, to make it more pleasant to author XML documents—especially articles and books.

Recent Comments