The topic of the fifth lecture in the RuG Metabolism & Nutrition course, delivered by Hans Jonker, was regulation of energy metabolism, detailing how the body maintains the homeostatic balance between energy storage (when feeding) and energy burning (during fasting or exercise).

According to Hans, the balance of fats, carbs and proteins in our diet should be < 30% fats (9 ca/g), 50–60% carbs (4 ca/g), and 10-20% proteins (4 ca/g). (1 kJ = 0.24 calories)

Most people need at least 1800 kcal/day, of which only 20% is spent on activity, 10% on digestion and 70% on our basal metabolic rate (BMR). The average energy intake in many developed countries, however, is much higher. In the NL this is 3240 kcal. In the US this number is even worse, at 3770 kcal! Contrast this with Ethiopia, where it is only 1950 kcal. (Mean BMR (70% of E expenditure on average) is 1500 kcal, in the range of 1027–2499. Corrected for lean body mass, the difference between 1075 – 1790 = 715 kcal, the amount of calories that you would burn during a 10km run!)

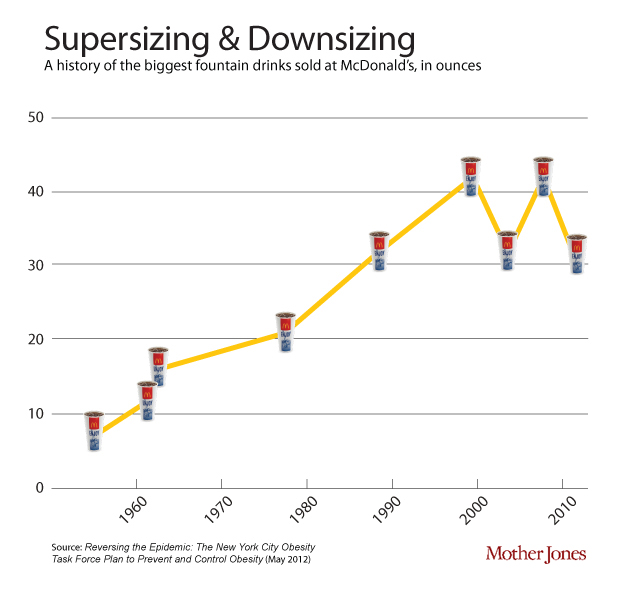

One of the contributors to the discepancy between calories in and out is that portion sizes have gone up since the 1950’s. This soft-drink diagram is taken from Mother Jones.

A genetic make-up that predisposes many people towards energy efficiency and towards overconsumption during ‘fat times’ (thrifty gene hypothesis), combined with the current abundance of calory-dense (high fat & sugar) food, the proliferation of life-styles that do not require sufficient exercise and other environmental issues can cause metabolic syndrome. Metabolic syndrome is characterized by at least 3 of the following conditions: obesity, high blood sugar, high chol. (LDL), high blood lipids (TG), and/or high blood pressure. A range of metabolic diseases are likely to follow metabolic syndrome, such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and many types of cancer (e.g. prostate, colon, breast).

Metabolic processes can be divided in anabolic (synthesis) and catabolic (break-down) processes. Depending on the availabel nutrient supply, the body can be said to be in an anabolic state (of energy storage), during which sugar is burnt or a catabolic state (of energy utilization), during which fat and/or amino acids are burnt.

During feeding, first, bile acid (BA) production goes up and the gall bladder empties. Then, the production of leptin and CCK signal to the brain that it should (start to) feel satieted. Meanwhile, the rise of glucose levels causes the release of insulin, which signals to cells throughout the body to take up the glucose. Some excess glucose is converted to glycogen (glucogenesis), the rest stored in adipose tissue as triglycerides (lipogenesis). When overfed, adipogenesis, takes place. Adipogenesis, the differentiation of pre-adipocytes into mature fat cells, is the means by which new adipose tissue is created.

Postprandially, during fasting, ghrelin production increases appetite. BA production goes down as the gallbladder fills. When glucose levels fall too much, glucogenolysis breaks down glucogen into glucose. After this glucose source runs out, amino acids are converted into glucose (gluconeogenesis). Most tissues can also derive their energy from fatty acids, which become available during fasting by the lysis of triglycerides (lipolysis). The brain and red blood cells, however, can only be fuelled by glucose.

Prolonged fasting (starvation) will trigger ketogenesis, the production of ketone bodies from proteins to supplement the waning free amino acid pool. Eventually, torpor (hibernation) will set in.

Nuclear receptors

Ligand-activated transcription factors are nuclear receptors that, when they bind to ligands (steroid hormones in this lecture), enhance or inhibit the transcription of certain genes. All these receptors are very similar. The family is larger than just those that bind to steroid hormones (e.g.: similar receptors have been found to bind to vitamins), such that 13% of FDA approved drugs target NRs. (For unknown reasons, C. elegans has more nuclear receptors than H. sapiens. Plants have none.)

Ligand-mediated activation: NR binds to HRE (Hormone Receptor Element), a stretch of DNA to which also an RXR receptor is bound. This complex is bound by SMRT/NCOR complex, actively repressing the HRE. When a ligand binds, it displaces the SMRT/NCOR (HDAC co-repressor) complex and the receptor complex (with the ligand) can bind to another protein complex (HAT co-activator complex), which causes acetylization of a DNA region adjacent to the HRE. (HDAC = Histone Deacetylase; HAT = Histone Acetyl Transferase.) Acetylization activates the genes.

NR example: enterohepatic circulation of bile acids

FXR (farnesoid X receptor) is also known as the bile acid receptor. FXR is expressed in the liver, which releases bile salts. Bile, produced by hepatocytes (liver cells) ends up in bile ducts, aided by 3 ABC transporters of relevance: ABCG5/8 transporters (for cholesterol), MDR2 transporters (for PC), and BSEP transporters (for BA). Bile is made up of 4% cholesterol, 24% PC and 72% BA. PC helps to neutralize BA so that it doesn’t damage cell membranes.

BA reenters the cell with the aid of a transporter called NTCP. Cholesterol also enters the hepatocytes (liver cells) (LDL through LDLR, HDL through SR-B1).

FXR activation triggers the release of bile from the hepatocyte. In enterocytes (in the illeum, the final section of the small intestine), FXR downregulates the uptake of BA by ASBT transporters and stimulates the release of BA by OSTa/b. FXR is also responsible for the release of bile salts from the illeum into the capillaries. Bile salts are also released into the blood stream by the gallbladder, which constricts under the influence of CCK.

LXR and FXR

FXR (farnesoid X receptor) is activated by bile acids, whereas LXR (liver X receptor) is activated by cholesterol.

In the liver, LXR activates ABCG5/8, inceasing the release of Chol+BA by hepatocytes. This, in turn, lowers cholesterol, as well as atherosclerosis, but also raises triglyceride production. LXR is thus a promising target for treating atherosclerosis, with the unintended side-effect of weight-gain. Indeed, a synthetic LXR ligand (GW3965) has been found to inhibit the development of atherosclerosis in LDLR and apoE knockout mice by S.B. Joseph et al. (PNAS 2002;99:7604-7609). And, indeed, the treated mice gained weight as well.

FXR activates MDR2 and BSEP transporters (which facilitate the release of PC and BA, respectively). FXR lowers cholestasis, the incidence of chol. gallstones, and the production of triglycerides; as a target for weight-loss, the unintended side-effect will be atherosclerosis.

The role of LXR & FXR in the regulation of hepatic lipid metabolism

Triglyceride (TG) from the diet or adipose tissue is hydrolysed (lipolysis) into free fatty acids (FFA), which enters the hepatocyte through the CD36 transporter. FFA in the hepatocyte can be converted into TG and stored in a complex with cholesterol, or TG+chol. can leave the hepacotye through MTTP as VLDL. Alternatively, FFAs can be used in the FAO pathway for the energy necessary to produce ketone bodies during the production of Acetyl CoA.

LXR activates lipogenesis (FFA synthesis from sugars) and increases FFA uptake from the blood, causing more TG production, which is dependent on [FFA]. ABCG5/8 transporters are also activated, increasing the release of Cholestorol and BA into the bile ducts. FXR, however, inhibits LXR and also directly inhibits lipogenesis.

PPAR (fatty acid) receptors as drug targets

Besides the FXR and the LXR receptors, to which, respectively, bile acids and oxysterols bind as ligands, Hans also treated the PPAR (Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor) family of receptors, which bind to fatty acids.

PPARγ is implicated in energy storage. PPARδ and PPARα are implicated in energy burning.

PPARα has been a drug target since the 1950s. It is activated during fasting (by PUFAs or fibrates), when it causes the burning of FFAs (through the FAO pathway) and inhibits lipogenesis. HDL goes up, while TG and FFA go down. Kersten et al. (in The Journal of Clinical Investigation 1999; 103(11):1489-1498) describe an experiment with PPARα knockout mice, which develop steatosis and hypoglycemia.

PPARγ (also an important drug target), is activated by lipids in the diet, stimulating the “energy storage” gene program, causing adipogenesis, lipogenesis, and adipokine secretion (adiponectin). When activated, PPARγ lowers blood glucose and sensitizes to insulin, making Avandia one of the top diabetes drugs in 2006. Bad press, that users might potentially suffer an increased risk of heart attacks, has made these drugs less popular.

PPARδ function remained unknown for a long time. It didn’t help that knockout mice died while still in the embryoic phase. The solution was to construct mice (VP16-PPARδ mice) in which PPARδ is only locally overexpressed, in muscle. VP16-PPARδ red muscle mass increased relative to controls.

The difference between red and white ‘meat’

| Type I fibers |

(slow twitch), |

oxidation |

(fats), |

slow fatigue, |

long distance, |

“red meat” |

| Type II fibers |

(fast twitch), |

glycolytic |

(sugar), |

rapid fatigue, |

sprint, |

“white meat” |

Transgenic mice with increased PPARδ in their muscles were true “marathon mice”. These mice are also overweight-resistent, which makes PPARδ a promesing anti-obesity drug-target. It as already used as doping by cyclists.

[See Slide 29 & 50 for a nice overview of the exam material from this lecture. Slide 29 would be nice to include here and Slide 50 would be nice to work into the introducary part of this post.]

The lecture ended with a nice citation of Mark Twain: “The only way to keep your health is to eat what you don’t want, drink what you don’t like and do what you’d rather not.”